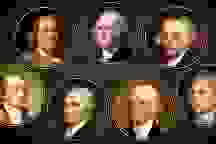

Sixteen years ago, in this newspaper, I tried to answer a perennial question about American politics. Does the United States look more like the country predicted by Thomas Jefferson, or by his rival, Alexander Hamilton?

Jefferson asserted that ordinary people with sufficient education and virtue can govern themselves wisely, that liberty is the natural desire of all mankind, and that the world's monarchs and dictators will ultimately be overthrown. On the other hand, Hamilton claimed Jefferson's view was folly, based on wishful thinking, because human nature precludes the kind of wisdom necessary for self-government. In short, Jefferson speaks to our hopes; Hamilton speaks to our fears.

In 1992, I concluded that America, and the world, reflected features of both men's views – their great philosophical fight lay unresolved. Today, Hamilton clearly has the upper hand.

Before the Constitutional Convention met in 1787, Hamilton observed the activities of a few state legislatures and concluded: "The inquiry [of legislators] constantly is what will please, not what will benefit the people." But he went a step further: It's the people themselves, not the legislators, who are to blame. The people, he said, "murmur at taxes, clamor at their rulers," but then elect demagogues who appeal to our worst instincts.

Over the years, Jefferson became less optimistic about the wisdom of the people. Still, in the last letter of his long life, he summed up his life's vision: "All eyes are opened, or opening, to the rights of man." He hoped America's experiment with democracy would be "the signal of arousing men to burst the chains under which monkish ignorance and superstition has persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings and security of self-government."

In 1992, it was still possible to believe Jefferson's prediction could one day come true. Many among us thought that the "blessings of freedom and democracy" might ultimately reach all areas of the globe. But 16 years later, can we still believe this? I think most of us have moved at least slightly toward Hamilton's darker view of human nature. Can we still believe, for example, that Jeffersonian democracy will one day arrive and then survive throughout Africa and the Middle East? The painful failures of the Iraq war have sowed substantial doubts: "Looking back, I felt secure in the knowledge that all who yearn for freedom, once free, would use it well," wrote Danielle Pletka in The New York Times recently. "I was wrong. There is no freedom gene ....".

History suggests that culture, not genetics, determines fitness for democracy. And history suggests we can pinpoint what kind of culture is required – a culture of the Enlightenment.

We in the West take the Enlightenment for granted. But it took centuries of brave, stubborn people, beginning in the 16th century, to push back against the ignorance and superstition in which all mankind had lived, to bring forth in isolated centers of learning a world based on reason and logic.

Here is a thought experiment to put things in perspective. Imagine a map of the world in 1800. Color in all the countries that took part in or were directly influenced by the Enlightenment (let us say, England, Ireland, Scotland, France, Italy, Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Slovenia, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Greece, Spain, Portugal, Italy, the Netherlands, the US, Canada, and the Scandinavian countries).

Now jump forward two centuries and color in all the countries with working democracies. It is virtually the same map. Every one of those 22 nations (or their derivatives) today has a working democracy. And how many countries have a fully functional democracy but were not among, or did not spring from, those 22 countries? Just four: Japan, Australia, India, and Israel.

What does this tell us about the Jefferson versus Hamilton question? In a Hamiltonian world, democracy will always be a precious commodity – sustained, and even desired, only by people whose cultural history includes an enlightened viewpoint or something close to it. The Enlightenment was a kind of miracle and not one we should take for granted.

Indeed, if Jefferson returned today, he would be shocked by the reemergence of self-styled Christians hacking away at the wall between church and state. Hamilton and Jefferson were deeply affected by the Enlightenment's emphasis on reason. Still, Hamilton believed reason would always be under attack by demagogues who know hate and fear are more potent motivators than reason and rationality.

Why do I take a darker view than I did 16 years ago? Today, we have a coarser public discourse and lower standards. We have suffered the consequences of a political party that quite openly set about to divide Americans into hostile camps because it believed that strategy would give them a narrow electoral advantage. The result is an atmosphere in which it is almost impossible to have a mature, adult, logical national debate about important issues.

Maybe Hamilton was on to something. Is democracy a natural state of mankind? Is the survival of democracy assured even in the United States? It is a sign of our times that we cannot be sure the answer to these questions is "yes."

(This article has appeared previously in the Chrtistian Science Monitor)