“Janet,” A whiney voice in the blackness of the tent. “Janet.”

I open my tired eyes. “What now Barbie?”

“I hear the horses. I’m sure they’re out there. And I have to wee wee. I’m afraid to go outside.”

Wee, wee. A grown woman, mid twenties, maybe older, saying wee wee. It’s ridiculous. “So you want me to go with you right?”

“Please, Janet. Pretty please.”

Damn. I unzip my sleeping bag. The desert air is chill. I fumble for the flashlight and aim it at the tent zipper so Barbie can get herself into the open air. “Put your shoes on,” I say. “You don’t want to step on a cactus.”

Moonlight touches the tops of the tents, slides across the wide water of the Rio Grande, sketches the line of canoes on the bank, and outlines the dark hills on the Mexican side. From upstream comes the whinny of horses, the wild horses of the Rio Grande. Occasionally, during the past week on the river, we glimpsed small herds of the heavy bellied, piebald animals. They raised their heads to stare at us, their eyes mild with a blank curiosity. Sometimes, they would whinny, stamp and turn, splashing along the shallows and disappearing behind the stands of carrizo cane that line the banks. They never came near our campsites and, our guide, Elizabeth Trenchard, assures us they’re shy of people.

“Why is it so stony?” Barbie’s stumbling, her feet half in and half out of her pink sneakers. “Why didn’t we camp at that place with the nice sand?"

“You can’t camp at the mouth of a side canyon. Rain far up in the hills could send down a flash flood.”

“Ooh, yuck, “Barbie stops. “Look at all the horse droppings.”

I swivel the flashlight. Dry horse turds the size and shape of Frisbees dot the area in front of us.

Old stuff,” I say. “Good fuel.”

Y’all so brave, Janet. I would never pick up those icky things like you do. You make such great fires.”

I almost replied, and you, Miss Southern Belle, do dick all, except change your clothes and put on make-up. Instead I pull her to one side before she walks into a barrel cactus. I’m getting very tired of babysitting Barbara Jean Rawlins. On our first day, Elizabeth suggested her as my canoe partner, the idea being I would brush up her canoe skills and review the rudiments of white water. Elizabeth took on the other newbie, a large and capable looking sixteen-year-old girl. The remaining two canoes are manned by seasoned canoeists, Texan gals, old hands on the river, who’d been on many trips together.

As I wait for Barbie to finish on the other side of a clump of tall carizzo, I wonder if I can put up with her much longer. She’s a fair canoeist who knows the major strokes but whenever the river picks up speed, she seems to fall into a doze, perhaps mesmerized by the roar of the water and the dark colours of the roiling current. The Rio Grande, placid and lazy along much of its length, can turn dangerous, taking on speed as it runs down hill, squeezing into narrow canyons, flinging itself against red cliffs, and, at every turn and twist, sending brown water roaring up the rock walls in dizzying waves.

Yesterday afternoon, going through a narrow canyon, I had to scream at her. “Barbie! Wake up and back paddle, damn it!”

In the stern, I was aiming for a back ferry, a move to keep the canoe at an angle to the current so that the boat would not be slammed into the side of the cliff. In the very fast water, I needed all my strength to set the angle and hold it in place. The bow person is supposed to back paddle like mad to move us across the current but Barbie just sat there, her paddle across her lap.

“Back paddle, you idiot or we’ll both drown,” I screamed over the noise of the water. Barbie’s shoulders gave a little shake and at last she set her paddle in the water. “Put your dam back into it.” We shot out of the canyon with inches to spare.

Elizabeth met us on the bank. Her voice was gentle. “What happened Barbie, Why weren’t you paddling?”

“Janet yelled at me.”

“Before that, honey, you were just sitting there like a little ole’ ornament.”

“I don’t know. I was scared.” She sounded like a ten year old.

“We have at least three canyons to go. Janet’s a strong canoeist but she can’t navigate these narrow spots without your help.”

Barbie sniffled. She looked at me. “You swore at me.”

I took a deep breath and stared at this child-woman, leaning on her paddle, staring into space. I tried to remove my anger from my voice. “Sorry,” I said. “I’m a Canadian. We swear,” and, I mentally added, especially before we die.

Safe on the bank, Barbie looked as cool as if she were setting out to the church picnic. On the other hand, my heart was convulsing. She had no idea of the danger she’d put us in.

On a smooth shallow stretch of river, we again practiced back paddling and draw strokes. Again, I explained that when the river runs fast and the canyon turns, the current could slam the canoe straight into a cliff. I drew a picture in the sand of a boat doing a back ferry. “This is how you avoid being flipped into the water because when that happens, the current could hold you against the wall and, if it does, you’ll drown.” She looked bored. Her mind seemed far away. I sensed she did not believe me. This Texas miss had obviously led a princess life. Nothing bad could possibly happen to her.

“Are you still game, Janet?” Elizabeth asked me later in her soft Texan drawl. “Can you carry on with her?” Elizabeth, small, blond, curly-haired, had been guiding for several years. She had written the book about canoeing the Rio Grande. I knew she was worried.

I considered. “I think so. I’ll just keep reminding her when we get near a canyon.”

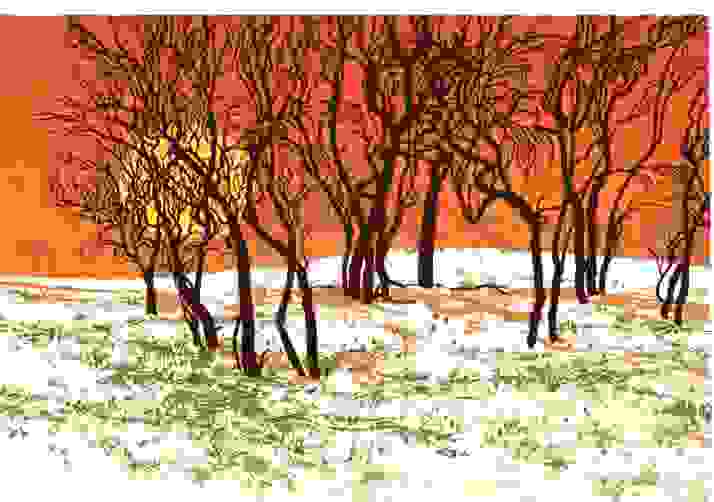

Now, outside in the first touch of dawn, I smell the sweet desert breeze carrying perfume from unseen flowers. A touch of sun edges the Mexican hills. This is beauty time, when the entire landscape glows colour: apricot, rose, rust, dark banded purple and gold. Once the sun is high, and it moves there quickly, the land sinks back into everyday brown until sunset starts the show again.

Barbie steps out from behind the cane. “Look across the river,” she says, her voice soft.

A man is standing on the Mexican shore.

“A illegal?” I feel a shiver of fear. Would a man who’d already walked through miles of desert be desperate for food or water, desperate enough to rob? Kill? “Could he be dangerous?”

“No, no,” she answers. “He isn’t carrying a pack. He’s here for another reason.”

The man is very still, staring at our tents. We’re partly hidden by the tall cane. He carries a coiled rope over one shoulder. The soft whinny of the horses upstream has him angle his head in their direction.

Barbie steps to the edge of the water. “Hola!” she calls.

I grab her by the arm. “What are you doing?”

The man answers in Spanish and the two shout back and forth.

“He’s coming over to get a few horses, is all,” Barbie says. “I told him that’s all right. We’re no danger to him. Just canoeists.”

A horse and rider appear on the far hill. I slide my feet backward in surprise and fear.

“Don’t worry, Janet. It’s his friend.”

The rider leads a second horse. The man on the shore swings up into its saddle. The two move slowly to the river’s edge, enter the water and quietly head upstream.

“He says this is the best place to cross,” Barbie says.

“Is it stealing, to take the horses?”

“I don’t know. Maybe. This is a national park so I’m thinking they’re protected. But you know, they’re poor, a lot of them.”

Elizabeth comes out to join us. “Horse thieves,” she says.

Even in the soft sand and mud by the river, we can hear the thuds of hooves. “Yip! yip! Hi! Hi!” yell the riders as they emerge from the unending cane, swinging their ropes, three riderless horses thundering ahead of them.

One minute, the captured animals are coming towards us, eyes rolling, manes and tails flying, snorting in fear and a few seconds later, they all turn into the river, water snapping under their hooves. On the far bank they become silhouettes in the newly risen sun: five horses, two riders, the dark snaking ropes. They disappear around a fold of hill.

“What will they do with them?”

“Pasture them somewhere. Then kill them and sell the meat,” Elizabeth says.

I ponder this as I eat my chili and tortilla breakfast. Such beautiful animals. The other members of the party seem unsurprised by the story. “I wonder if the park rangers keep a count,” the sixteen year old says. The others shrug.

My thoughts turn to the riddle that is Barbie.

Inside our tent, as we are packing our kit, I say, “That was a smart move, talking to that Mexican. I didn’t know what he was up to and I was pretty nervous.”

“Oh, most Mexicans are nice, actually. I figured out they were after horses. Perfect area, a shallow ford, lots of hoof prints on the far shore, lots of horse droppings around. They’ve been here before, I expect. Our tents must have been a surprise.”

“Thanks,” I say. “I’m sorry I swore at you yesterday. Maybe we’ll have a better run today.”

“Yesterday, I wanted to kill myself, Janet.”

What the hell? “Yesterday, in the canyon?”

She nods.

“And why? And also take me with you. Thanks so much.” My voice rose, half in anger, half in fear.

“No, no. I was thinking of jumping out.”

“Much good that would do. In that current, we’d have gone over and then wrapped against the cliff.” It takes all my willpower to shut up, calm myself and moderate my tone. “Well, I’m glad you changed your mind,” I say carefully.

“My husband died.”

I look at her. She’s married? I thought she was single. All I can say is “When?”

“Three weeks ago. He was twenty-eight. Liver cancer. He died in a week.”

Oh damn. I’m caught off guard. I sit back in surprise and stare at her. “I’m so sorry,” I finally say. “So then, you wanted to die too?”

“Not at first. I thought this trip would heal me. Help me get over it. But it didn’t work. All this sand, eating on the ground, using horse stuff for fuel. My clothes are filthy. I’m filthy. My hair is full of sand. I’m all sand, a sand person, a mud person, just going down a stupid, ugly, polluted river. I should just die too. Get it over quick. He’s gone so why not me too?”

I reached for her hand. “But you didn’t do it.”

“That horrible water, just brute ugly, I couldn’t.” She pauses as I move to sit beside her, put an arm around her shoulders. I’m out of my depth, not knowing the right words but I’m going to try.

“They took the young horses, the most beautiful ones,” she says. “They’ll die too. So I think now, I think, I can’t…”

Her voice turns into sobs. I hug her tighter, drop my cheek on her blond hair. “I’m so sorry,” I say again.

“I can’t add to it,” she says. “Death I mean.” I wait, feeling her sobs ease down. “Don’t tell anyone, please Janet, please. Especially Elizabeth. Promise, please.”

I hesitate for only a second. Do I have a choice? The only way out of here is by canoe. I must have this young woman’s cooperation; my life may depend on it and so I make the promise.

“Tomorrow we get to a big hot spring,” I say. “We’ll bathe, wash our hair. You’ll feel better.”

We take down the tent in silence, add it to the Duluth pack. For the first time, she helps heaving the pack on to her back and heads to the canoe. “We got married three months ago,” she says.

How can I answer? I just say, “Ah, Barbie.” I feel tears on my cheeks.

I walk with her carrying our daypacks. The sun is high enough to turn the world sandy brown again. Dragonflies crisscross the water. The air is flat with an edge of heat. Far off, I can hear the shushing sound of the next canyon.

The others are loading up, almost set to go. I push our canoe out and hold it as Barbie scrambles nimbly over the packs into the bow seat. She tucks her day back into the point of the bow and takes up her paddle, pushing the blade into the sandy bottom to hold the boat steady in the placid water.

Elizabeth gives me the thumbs up. She calls to Barbie. “How y’all doing? Ready for the day?”

“Fine,” Barbie says without turning her head. “I’ll be fine.”

Elizabeth and I exchange looks. We’ll be first in line today and this is comforting even though I know there’s little the others can do if the current overwhelms us. I set my daypack behind the stern seat. Bending forward, hands ahead holding the gunnels, I wade a couple of steps into the shallows before swinging my legs into the canoe.

“Okay, Barbara,” I call to her. “I’m ready.”

We push off into the river.