Matthew Youngblood carefully removed binoculars from his daypack. He trained them on the top of a finger of rock that stood, separated 30 or 40 feet from the southwest rim of the ridge that he was lying on, stomach down. The finger of rock was a column of sandstone, maybe 50 feet high, tapering upward and flat on top, piled with sticks.

The hike to this remote site had been prompted by his observation of a magnificent bald eagle hen that he’d been watching for several weeks. The burgeoning eagle population occupying high nesting sites near human settlements was becoming more common. General interest in the come-back of eagles drew readers. Matt had received recognition from the Colorado Audubon Society for his photography in local publications. He was the go-to photographer by bird watchers and ornithologists alike. Their appreciation of his eye and his dedication to his specialty made him particularly interested in this particular specimen.

As a kid, he had begun collecting bird nests in his backyard and neighborhood. After taking up photography in college, he had transferred his collection from real stick-and-mud nests to digital images and his collection had grown into the hundreds. The nests were incredibly diverse and varied in size, ranging from tiny hanging baskets of vireos to the treetop heronries of the great blue heron, where dozens of birds nest collectively.

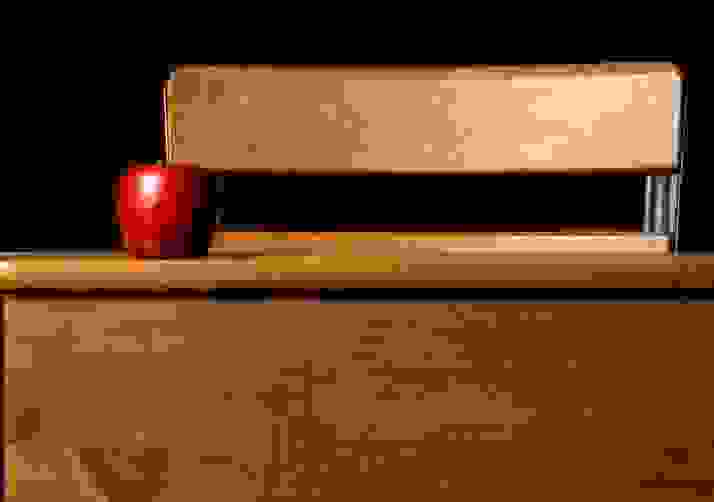

He also had several aeries in his collection, this one belonging to the largest eagle he had tracked yet. This nest promised to yield a load of useful information, as it sat atop a pillar that appeared to be more than twelve feet in diameter. The top of the pillar seemed accessible by climbing the 50-feet of nearly vertical sandstone using the rubble and cracked rock between it and the ridge on which Matt was lying.

He had made himself familiar with the eagle’s habits over the past few months and had noted that the huge predator usually left her nest as the eastern sky flooded with full morning sunlight, providing the first thermals of the day. With her young still in the nest, she generally was back in her aerie by noon carrying an unlucky small animal, a snake or a fish from the river nearby. Under Matt’s observation, the Queen of the Eastern Slope had recently enjoyed her daily meal at or near the site of the kill. Her chicks were grown and gone. Now she could cruise around and return to her aerie an hour or so later, preen and groom herself during the afternoon, and sleepily watch her kingdom from her majestic rock perch.

At this point in his observation, the eagle had been away from her nest just about a half hour. He made his final visual check to ensure there were no more fledglings still in the nest. The code of conduct proscribed by the Society discouraged any close contact with immature birds.

Matt double-checked the distant speck circling in the sky far to the south that was almost out of visual range. He stowed his binoculars in his pack and began picking his way carefully down to the base of the vertical crag looking for a stairway up the spire to the target of his photographic inquiry. The crag offered little resistance. Footholds and handholds appeared every few yards, and he ascended the spire patiently, noting possible complications for the climb back down.

His pulse quickened as his head cleared the rim of the stone aerie. Gripping the edge of the rock platform that was littered with with sticks, brush, feathers and bones, he noted the presence among the litter of clean white skulls of many sizes and species. This would be an excellent record of the bird’s feeding habits, he thought, and he immediately felt confident his photographs from this site would be some of the best he’d collected so far.

He pulled himself completely onto the sandstone tabletop, unshouldered his pack, and pulled his camera out efficiently, having repeated the maneuver hundreds of times. He concentrated intently on the camera’s small screen and clicked off a dozen shots of the nest as a whole. Then he carefully stepped forward into the litter and began to document more closely the eagle’s prey, knowing that it was the sort of detailed information that would fascinate the more serious ornithologists in the local chapter.

He stopped dead as he focused on a clean skull centered in his viewfinder. He moved the camera away and knelt over the skull to examine it closely with his naked eyes. It looked human, though small, only slightly larger than a grapefruit. He picked up a stick and carefully prodded the skull face upward. It was unmistakably the skull of a small child, with only two tiny teeth barely emerging from the upper jawbone. He snapped several pictures of the skull and stepped carefully around further into the litter and sticks. He concentrated on positioning himself according to the direction of the sunlight to continue photographing the aerie, but the impact of recording human remains sent a chilling sense of horror up the back of his neck, raising hairs as it went.

He focused on another pile of bones and felt the return of the chill as he found another skull. He stood up, took a deep breath, and struggled to clear his mind. The macabre scene at his feet was disabling his ability to think clearly. He looked in the sky to the south. He couldn't immediately see the eagle. He picked up his water bottle, bent forward and poured water on his head and face. He set the bottle down on the rock near his pack and picked up his camera again.

In the next few minutes, Matt documented the remains of six or seven human infants or small children scattered in the debris across the stone slab, which he now began to consider as something of a sacrificial alter. At one point he glanced over the edge of the table top on the side opposite the crag ladder and noted that the drop from that point was more than a hundred feet, and at the bottom a scattering of more bones glinted in the sunlight. He thought he could probably reach this other cache of bones as he descended if he could find a route down around the base of the spire. But, in case he was unable to find a way to the lower depository of carnage, he held his camera out over the shelf’s edge and snapped a few shots.

At the third click of the shutter, the sound of air moving rapidly through feathers filled his ears like a clap of thunder, and then, in the next moment, he felt the bruising impact of a 40-pound bird hitting the back of his neck at nearly 60 miles an hour. The impact instantly knocked him into the empty space over the bone pit far below. With the shock of the blow, he barely registered the pain that must have resulted from the talons tearing the flesh around his neck and face. And his revulsion at the horror of finding infant human remains was replaced by the more unspeakable horror of instantly knowing his own bones would be picked clean by the feathered ruler of the sandstone aerie.

. . . . . . end . . . . .