(for Charles 'Doc' Hyatt)

“Kennedy, Kennedy, Kennedy, Kennedy….”

The Eastside Theater’s sound system was playing “Tequila," over and over again. The Champs hit was hot shit at the time. The theater’s lights had gone up, the music started, and then just repeated. The movie flickered, faded, then stopped. Me and the fellas just sat there waiting for it to resume.

It wasn’t just another Saturday morning. This was one of those late winter days between basketball and baseball seasons when instead of playing ball all day, my boys and I were going to the movies—the late winter following a Thanksgiving month of seeing the President’s head shot off on network TV daily.

We kinda liked Kennedy. We’d all made a few bucks putting up his campaign signs around the neighborhood. He was an exception of sorts with us. Him and Mickey Mantle, and a cat named Grady.

This week we were off to the Eastside Theater, to see “Snow White and the Seven Dwarves."

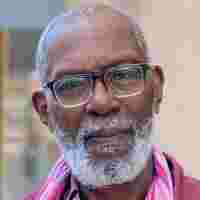

We’d planned it all week, dedicated days to hustling up chump change, in various neighborhood ways, and pooled the dough. So, Saturday we were all up early and out of the house. Me, Calvin, Mike, Rico, and Doc. Doc had banked the scratch as we hustled it up during the week. He was the best of us in Math; and, he had this thing for being fair, whereas the rest of us were somewhat shaky in that area when it came to money. So, Doc always banked the dough.

They all came over to my house, to get me out of the backyard garden where I started most Saturdays, regardless of the season, studying ants. I loved to follow ants. I was fascinated by their industriousness and organization. The way they kept on keepin’ on no matter what. Nothing short of death thwarted them in their relentless quest for…something. I never figured out what. It wasn’t about any individual one of them: For all their numbers, they were one.

No one ever told me that studying ants, entomology, was legit..; so, I let it go. It was easy, once I found out, observing my neighbor and occasional caretaker become Oklahoma University’s first African-American football player, you could go to college playing football. I didn’t see nobody going to college free for studying ants. And going to college was the only escape from beans and the Blues I could see.

It was many years until I came to understand my fascination with the insignificant if not nuisance insect, in an instant outside Santa Fe. The guys just figured I was weird. They called me “Prof". One of them had started calling me Professor because I wore glasses and spent a lotta time hiding out in the Dunbar Library, just to get away from all the crazy stuff goin’ down in the neighborhood.

As always, they came up the alley, whistling our signal, and we set out to troll the neighborhood, looking for money-making opportunities—we’d already made enough money for the movie the evening before, selling Roscoe Dungee’s Black Dispatch newspaper on the streets of our neighborhood. I’d even lucked up and sold 20 at one time to some of Duke Ellington’s orchestra, living at the Canton Hotel down on Deuce. They always set up camp there, when in town to play for the white folks’ dances.

And, jamming at the joints on Deuce in the wee hours after those dances.

But the extra change from a few redeemed soda bottles, or money found in the alleys and streets, lost by the various characters and drunks who spent their weekend nights in the joints which bordered our homes, came in handy at the snack-bar—especially since we were going to the Eastside, which had better but more expensive snacks than our neighborhood theater. The Eastside was across the alley from Dunbar Grammar School, from which I had recently graduated.

We usually attended The Jewel, a block away from my house: A mercifully fast sprint home on those dark nights after seeing “The Creeper” or “Wolfman” or “The House on Haunted Hill." The Eastside was out of our territory, a mile east, past Woodson School and Butler’s BBQ, where we pooled our Black Dispatch tips to buy boxes of rib-ends after we’d sold out of papers.

So, we always searched the alleys as well as the streets. Especially after me and Doc found a cloth sack full of money one summer night while playing hide and seek tag. We were crouched in the weeds halfway down the alley between Fourth Street and Third when the alarm at 7-Eleven went off. A minute later a dude came running down the alley with the bag in his hand. He threw that bag into the weeds right across from us and cut through a backyard.

We kept still, listening. We could hear the cops yelling for the guy to halt; then, shots fired. End of story, you dig. There were sirens and the usual arrest opera. Eventually, I crawled across the alley and found that bag. Me and Doc climbed a tree to the fire-escape of the apartments next to The Jewel and went through the apartments down to Fourth Street and home. The cops were beginning to search the alley.

$400 bucks! We never even thought about turning it in. Split it two ways, spit-shook on secrecy, and were the captains of our crew that summer, picking up the tab at the movies, Butler’s and our favorite hamburger joint, Grady’s, where grilled burgers were only twenty-cents. We bought Levi’s and Chucks for the whole crew. It was our best summer together. And, we made a few bucks distributing handbills and posting signs for Kennedy, Kennedy, Kennedy, Kennedy.

We had that cat all over the ‘hood.

We’d also learned that on the mornings after big shows, parking lots could be full of all kinds of booty. Two nights before “Snow White," the Ike and Tina Turner Revue had played the Golden Eagle, a joint on the far east side, on a street that tragedy would someday rename Martin Luther King Boulevard.

That night, Calvin, Mike and I rode our bikes down to check out our headquarters. We’d established a little camp out back of the Golden Eagle, between it and the railroad tracks that paralleled Route 66 through our community, from which we spied on the joint at break time. The bands always hung out and smoked back there.

On the morning after Ike and Tina’s show, Mike found a wristwatch with a cracked crystal in the parking lot, and Calvin found a Zippo that looked like it had been run over but still worked. I found a silver dollar, oddly not lying flat, but standing on edge in a crack. It was strange. I kicked it. So strange, in fact, I still have it. Things were looking good for the Saturday morning movie.

Premier movies were usually years old by the time they made it to our neighborhood theaters. Movies for children were rarely screened, as they were not as cost-effective as westerns, or mystery, or even horror flicks. That’s what made “Snow White” special. It was only for us and relatively exotic to us.

Miles had recently covered “Someday My Prince Will Come” in his own inimitable way. The cat who owned our neighborhood pool hall, Mr. Brown, had played it for us one day after school. That’s the way I first heard about the Disney film. It’s also the way I learned about “The Sound of Music," years later, when John Coltrane recorded “My Favorite Things."

Mr. Brown always made us listen to his jazz records while we shot pool after school. He took it very seriously; so, we figured it was important, and took turns paying attention—when we weren’t taking a shot.

But, that was the way the larger culture reached the world we grew up in, filtered through our tenuous connections to the larger world beyond the invisible walls around ours: Those who adventured beyond the boundaries hustling to make it back with “crusts of bread and such," Brown’s Poolhall, various beauty salons, barbershops and two-year-old movies. Hell, I thought Lester Young was President of the United States until Eisenhower beat Stevenson. That was the first time I realized I was living some kind of reality running parallel to the rest of the world in which ‘Prez’ was probably an enigma.

It was called “separate but equal." Not that I knew it at the time.

Whatever it was, we were about to get our equal opportunity to escape our sepia-toned lives on the border of a segregated business/red-light district, into Walt Disney’s fairytale world.

I loved those cinema escapes. They were a peek into another way of seeing and being: Hints of something more, somewhere beyond. I got a feel for that ‘somewhere,' many nights lying in my bed, gazing out the window, listening to my crystal radio and searching the night sky for planes. Wondering where they were bound, and resolving to, someday, get myself wherever that was.

Our routine was well-established. We bought our tickets at the box office window, then stopped at the concession stand to stock up on our first-course of popcorn and soda, maybe even copping our dessert course at the time—if the flick promised to be particularly compelling.

For “Snow White," we seated ourselves at the back of the main floor, center, against the wall. We could see the whole audience in front of us as well as the big screen. I remember the previews and snack bar commercials, the anticipation and, finally, the thrill of entering into that separate but equal place of disbelief suspended. Our fantasy lives were amazingly meager, and we had no clue of what we were missing. Everyday life was all too real for us, and it was all, always, black and white, except for the assorted characters, their language, and their blood.

The fairy tale notion of a pretty white girl being cared for by a troupe of dwarves with funny names was just far out enough to give us psychic distance from the domestic drama and vice we witnessed daily.

We took our seats, there was a Heckle and Jeckle cartoon accompanied by Charlie Parker music, the big lion roared, and the movie began. I don’t remember exactly when, but I was sitting closest to the aisle and at some point early in the story I felt, as much as saw, the shadow of someone flash past me. There was danger in the energy of that movement. I felt it, but I was so involved with the film that I ignored that instinct.

Snow White was charming the dwarves. They were so charmed they were whistling while they worked: A novel notion where I grew up, even for a 6th-grade kid. But it looked like those cats always did it; and, loved it.

What followed that passing shadow was a pantomime in silhouette. It stopped down the aisle at a row where only one person was sitting, low in his seat. Alarmed, the silhouette seated there rose halfway up in his seat. The shadow drew a pistol from its belt and took aim. The silhouette drew his hands up in front of him, and said “Please!”

He backed away a step and fire flew from the shadowed gun. “Please." he said again.

The orange-red of the shot and its sharp report tore me away from Snow White’s birdlike singing, abruptly switching my briefly suspended-disbelief with a familiar rush of adrenaline. Everything got very clear, very fast; then, slowed way down. I watched the shooter walk away amid the fleeing audience.

Unfortunately, this was not my first murder. I don’t think it was Calvin’s first either. And I know it wasn’t Rico’s.

I’d felt this rush the first time several years earlier, standing on the curb playing cars one summer night, trying to shout “That’s my car," before Rico and his sister, Rita, thus claiming imaginary title to the passing vehicle of my choice. We lived just off old Route 66, before the construction of the freeway bypass, so there was a steady stream of cars to choose from on a Friday night.

But, there was also a fight starting up that night on the corner under the streetlight where the teenagers sang harmony on weekends. Two men were arguing profanely, and before we could even react by backing away into my front yard, one of the men snatched a straight-razor out of his pocket and slapped it across the throat of the other.

Everything froze; then, melted into slow-motion. The guy with the razor turned and walked away. The other man scratched his throat where the razor struck, and blood gushed out. He staggered across the street and collapsed on the bench at the bus stop. That was the first time I felt that surge of adrenaline I came to identify with surviving. That survivor’s, “It wasn’t me, I’m still here” rush.

As I grew older there’d been other experiences similar to this violent pantomime being played out before a backdrop of the radiantly cheerful Snow White and happily whistling dwarves.

The gunshot set off panic in the theater. Everyone ran for the exits, many of them screaming at the top of their lungs. Everyone, that is, except me and the guys. We just sat there watching the shooting, the resulting panic and “Snow White." Then, the lights came on.

The lights came on, and the sound system started playing “Tequila." But, the movie continued barely visible on the screen for a while longer. The moment was unforgettable. I liked “Tequila." It was a hit on the radio at the time. The tenor sax on the tune was the definitive rock and roll saxophone growl. The syncopation of it was infectious. I dug it the first time they played it that day.

I even liked it the second time through, although that’s when the screen went blank. By that time, sirens were wailing outside and people were coming in to check on the cat who’d been shot.

We sat tight, low in our seats and waited. The officials went about their business, and “Tequila” continued on a loop. I was soon tired of hearing it.

The ambulance guys rushed in and went to work, followed eventually by a couple of cops. White law: serious shit. We were old enough to know that white police in our community was to be taken with serious caution.

The cops looked around and asked a few questions of those who weren’t able to get out. As they started to come back up the aisle, one of them spotted us, sitting there on the back row against the black wall, waiting for “Snow White” to resume.

“What the hell do you boys think you’re doin’?” one cop snarled.

All the guys looked at me. I was the youngest in the group, but as its bookworm, I was its default spokesman and negotiator.

“We’re waitin’ for the movie to come back on,” I replied. The guys nodded, agreeing, meeting my eyes approvingly. The cops laughed.

“Well, son you’ve got a lot of sand,” he said. He was a big man, red-faced and white-haired, with a friendly smile. His blue eyes were mean and betrayed his smile.

“But, I don’t think you’re gonna get to see the rest of this movie today. Can’t imagine why you’re interested in it anyway. It don’t have a damn thing to do with your kind.” He was still smiling. He pulled a dollar out of his pocket and dropped it in my lap. “Now, you boys get on outta here and let us take care of our business.”

I put the dollar in my pocket as I stood. We filed out into the lobby, then into the early afternoon sunlight. Suddenly the movie-house magic vaporized into our day to day reality. Coming out of movies as a kid, I used to enjoy the feeling that everything inside me had changed in the theater, while nothing had changed out on the street. I didn’t have that feeling coming out after “Snow White." Nothing had changed, inside me or outside.

We paused on the sidewalk across the street from the theater, behind the crowd gathered there to gawk at the drama from which we’d just emerged.

“What happened?” a woman asked.

“Somebody got popped at the Eastside,” a man answered.

“Oh,” the woman sighed, “Will it never end?”

“Not no time soon, Maddie," he said.

“Well, what are we gonna do now?” Calvin muttered.

Doc suggested there was still time to make the matinee at the Aldridge Theater down on Deuce. But, Rico said there was a Tarzan movie showing there. We’d agreed to stop watching Tarzan because he was always whipping ten or fifteen African warriors asses all by himself. And we knew that was pure bullshit.

The fact was, we knew that most of what we saw at the movies was bullshit. But, there was some shit we just were not going to suspend our disbelief about.

We decided to spend the cop’s dollar on hamburgers at Grady’s. That dollar and our change would buy us five of Grady’s delicious onion-grilled burgers and orange sodas. So we set out walking to the diner. The thing about Grady’s was he had never practiced Jim Crow laws. If you had a quarter, you were good for a burger, whoever you were. Grady never looked up from the grill anyway.

People said Grady was some kind of hero: Something about Omaha Beach. But Doc said there wasn’t no beaches in Omaha. Whatever the case, Grady had a neat converted Airstream diner with a cool stainless steel counter fronting red, padded stools you could spin around on. The diner was situated diagonally across from the University Hospital complex where most of us had been born. Halfway between it and the junior high school we attended, named after Frederick Douglass Moon.

We walked along in silence for a few blocks. I wonder who got popped, Mike said.

“Nobody got popped, Mike,” Rico snapped, “A man got shot.”

“Yeah, a man, for real,” Calvin added.

“Like what happened to Kennedy.” Rico added angrily.

“Some cold-blooded shit.”

“Yeah,” Doc almost whispered, “In slow motion”. “What was that he kept sayin’?”

“Please,” I answered, “He kept sayin’ please."

“One of the magic words,” Calvin said. “And, thank you. He didn’t say thank you.” He kinda laughed, ironically.

“That ain’t funny, Calvin.” Rico muttered.

Calvin was the oldest. He knew and did everything first. He wound up being the first of us drafted into the war. Years later, when I learned what a cynic is I thought of Calvin—who survived his tour in Vietnam with relative ease. He might’ve helped save my life.

You see, we all pledged Marines. We wanted to be like Sidney Poitier in “All The Young Men”: Black heroes, doing our ‘duty’. And, go kill the enemy: Whoever that was; because, there was bound to be one. The rockets had to red glare somewhere, you dig.

But, years later, in ’68, I got a letter from Calvin mailed from Long Bihn jail in Vietnam. In it he’d said that he was locked up for refusing to go out on point again while patrolling. He said brothers were always being chosen to take the dangerous point-position on patrol; and, after being picked several days in a row, he’d just refused to do it. And was arrested and jailed. I’ll never forget he finished that letter by saying “Forget the pledge! Do not come over here. If I see you here, I will shoot you myself.”

That did it for me and the Marines. And Vietnam was out of the question. Because Calvin always meant exactly what he said. His word was his wealth.

“Wonder what “Snow White” was about?” Doc wondered randomly.

“I don’t know, but I think that cop was right," Rico responded.

“Bull!” Calvin said.

“Whistle while you work,” I thought out loud.

“Yeah, what kinda shit is that?” Doc said.

“King Kelly whistles while he works.” I remembered.

“And he’s the King of the Shoe Shine,” added Calvin. “What does a lotta sand mean?”

“Don’t know, but it’s worth a buck, at least," Doc replied.

I’d been thinking about the so-called ‘future’ recently.

My teacher had been bugging us about what we were going to do with our futures if we didn’t learn the Periodic Table of Elements. She insisted that if we didn’t, we would end up living down on “The Whores’ Stroll.” But my house was right off the corner of the busiest corner on the whores’ stroll, so I never saw why I should care about the Periodic Table of Elements.

Suddenly, everything seemed unforgettable again. For just a few heartbeats everything took on a kind of sepia tone, and I paused taking a long look at each one of my friends, memorizing them. For some reason, I felt as if I’d better be right there, right then.

“Wake up, Professor. You sleepwalkin’ again?” Calvin said, snapping his fingers in my face.

“That cop ain’t ever heard Miles play that song from “Snow White." I mumbled.

“Y’all remember when Mr. Brown played that record for us?”

“Yeah,” Mike answered excitedly, “That’s the only reason I wanted to see the flick.”

Someday, Mike was going to become a great drummer. Calvin was pretty good, too. Because of those two, we all carried drumsticks around a lot. We’d drum on everything. They were good for self-defense, too. It was Calvin who first weaponized them.

“So, that’s what “Snow White” got to do with us, huh?!” Rico concluded. “Whistlin’ while you work?”

“Naw man, that’s what we got to do with “Snow White," Calvin said.

We climbed the steps to Grady’s, went in and took our places on the red-vinyl upholstered stools on which we’d spun since our $400 summer of ’61.

“What’s your pleasure, Gents?” Grady asked, smiling. He always called us Gents. Grady was a creature of habit and hard work, kinda like an ant. And, he always seemed happy. His smile reminded me of the cop at the Eastside, but, unlike the cop, Grady’s kind blue eyes agreed with his smile. The cop had an executioner’s smile.

“The usual, Mr. Grady,” I answered pulling out the cop’s buck. The guys nodded, voicing approval and kicked in their change.

“Lunch is on the house today fellas.” the old man said.

“Say what?!” we chorused.

“What.” Grady cracked back immediately.

There’d be no disappointing surprises at Grady’s. It turned out to be just another Saturday after all: The usual. Except, for the unexpected free lunch; which never tasted better, and almost erased the memory of the movie madness: Almost.

After giving Grady’s best the justice they deserved, we headed home. Each of us saying his goodbye, and peeling off as we got to his corner. Finally, I was on my own, my street being the last on our way. I got to thinking about the incident at the Eastside: Mostly about the sound of that guy begging for his life. Nothing else sounds like that. Nothing: Except, maybe, Ray Charles Wailing the word “Well," at the outset of some heartbroken Blues.

But the irony of the music thing struck me, too: The “Tequila” loop. I’m uncomfortable with repetition in general. But, the repetition of that particular tune, at that particular time, seemed somehow particularly cursory—if not downright vulgar. A one-word hit song. It stuck to me in an Ecclesiastical way.

Now, whenever I hear “Tequila," I think of “Someday My Prince Will Come”, my homeboys, Snow White and her boys. And, oddly enough, Grady, and an Omaha Beach I can only imagine in unguarded instants. How many hundreds of fathers, sons and brothers whispering “Please?"

“It’s the same old story with a different name …," according to Mark Knopfler

The first time I heard that line, I had to sneak off and cry.

I’m thankful that I don’t have to sneak away anymore.