“Maybe Jo Nell would know,” Mom said when I asked about my Other Brother.

Jo Nell was Dad’s cousin. They were brought up together like siblings, and I’d spent uncounted summer weeks and holidays weekends exploring Bristow’s redbrick streets with her daughters. In those days, Bristow had a Main Street, on which Jo Nell’s mother, my Aunt Aline, and stepfather had a hardware store and the Rexall Drug Store still had a chrome soda fountain. Coming from the larger metropolis of Tulsa, I was amazed to be able to buy a fountain Coke for a dime. And in Creek County, I was Karen June, just like Dad was Jim Ross.

“Karen June and Jim Ross are here,” Jo Nell’s youngest daughter once called as my family, including my mother and brothers, climbed out of our car.

“Karen June, you’re one of the Lee Girls,” my great-aunties told me.

The Lee Girls: My grandmother June and her sisters: Toke, Aline, Jackie, Nedra, and their brother the penultimate Ross, were known for their brown eyes and turned up noses, which they inherited from their mother, my Great Granny Lee. Like them, Jo Nell and I had inherited these traits. Jim Ross had the nose, but his eyes were more of a greenish hazel.

“Don’t let her out in the rain without an umbrella,” joked Aunt Toke after I was born. “She’ll drown.” She took care of me when I was very young. A hazy image lingers: me in a corner of the kitchen in our house in West Tulsa talking to a woman in a dark blue, white-spotted dress who stands at the stove. A fond feeling for blue, white-spotted dresses persists.

I’ve been told I took my first steps to Great Granny Lee, and I spent days at Aunt Jackie’s house in the country outside Sapulpa. She would hitch the Shetland pony to a cart and hand me the reins. “King’s your horse,” she said, and I whipped him up and down the gravel road. Her daughter Jan introduced me to the glories of steam curlers and did my hair, drove me into town for treats at the Dairy Queen.

I was in my thirties when one of Jo Nell’s daughters said, “Did you know King, my horse, died?” I hadn’t thought of King for more than a decade, yet I needed a minute to process my shock. Her horse? King was mine!

Because the First National Bank of Sapulpa gave Dad a loan when the Tulsa banks wouldn’t, it was our bank. Often after the drive-through, we stopped at Aunt Jackie and Uncle Gus’s grocery store down the block. “Take a candy bar,” Aunt Jackie said from behind the cash register. “Any one,” she said when I hesitated.

When Nedra returned from California, she was delighted to know I’d married an artist and told me all about her once-upon-a-time job hand-coloring photos.

So when Mom said she’d call Jo Nell, I said great. When she said we were going to visit her in Bristow, I said thanks.

Jo Nell’s redbrick mansion in the center of town had been sold decades earlier, and a newer, smaller home built close to the highway. She asked if we were okay eating in the kitchen. She wanted to stay near her dog, who was ailing.

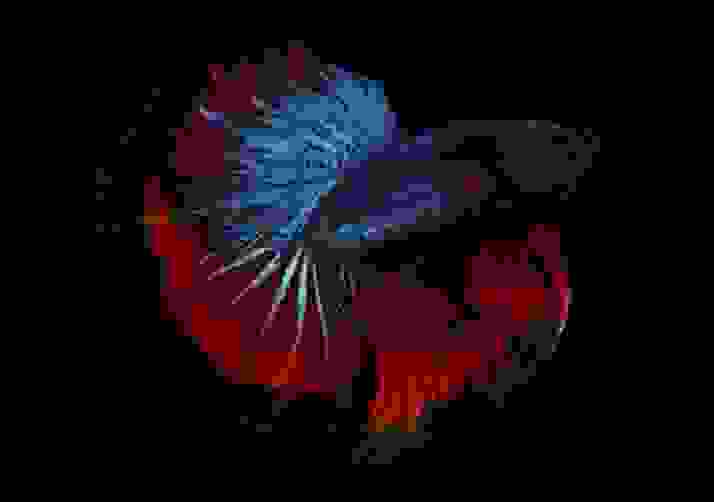

We said that was fine. No need to be formal for a lunch of cauliflower soup and salad. No need to create extra work for an eighty-five-year-old woman. Besides, sliding glass doors by the kitchen table provided a good view of her backyard, and cardinals were flocking to the bird feeder. She said cardinals often appeared in her backyard, a sign I thought that she was energetic, loving, and ready to help others, namely me.

The conversation was friendly until Mom surprised me. “Tell the family stories,” she said. Jo Nell’s mouth firmed. She took a breath and said, “Luther was a crook.”

Luther? I’d never met him, but I knew he’d once been married to Aunt Nedra. They left for California in the dead of night Jo Nell said, but she left out the details, like how the wall of the Christian Church in Tulsa collapsed, and that Luther had been the contractor.

Mom said Luther and Nedra’s son Jim Al had walked out of my parents’ house with her record player. Jo Nell added that even Nedra had been known to take a good coat that belonged to Uncle Gus, and she had no idea where Toke’s son Robert Lee was, nor did she want to know. She gave opinions, but no details, no stories, nor did she connect these opinions to Dad.

“Tell about Dooley’s,” Mom said with enthusiasm.

Jo Nell said my great-grandparents had a little store. Every evening my great-grandaddy Lee emptied the old-fashioned cash register and left the drawer open. Jo Nell and Jim Ross would look in the drawer and find two nickels or two dimes. “Jim Ross would ask, and Grandad would say, ‘oh you take ‘em.’”

Finally a sweet scene of the cousins, spending their nickels and dimes at Dooley’s soda fountain! A glimmer of their connection and why Dad loved his Granddaddy Lee.

“Tell about the little structure on the back lot,” Mom said. “Tell about wiping the dew off your faces in the morning.”

“Oh, you just wiped it off,” Jo Nell said in a dismissive tone. She demonstrated with an impatient swipe from her forehead down. “No big deal.”

I caught her impatience but didn’t understand it, and she quickly recovered.

The little structure was a screened-in building, where my grandparents slept on hot summer nights. But if any trace of it or the chicken coop or the barn where they kept my father’s horse remained, I never found it. Grandad died when I was six. That spring, I’d just discovered the daffodils in his front yard and the patio furniture stacked under his back porch. I’d just learned the gate in his fence led to the overgrown lot behind his backyard. Then Dad sold the house on Union Avenue. If he ever mentioned having a horse, I have no memory of it.

“What else?” I asked.

“Toke’s husband worked in the oil patch,” she said. “She used to say the smell of the refineries smelled like money.”

So many things have changed, even disappeared, but in West Tulsa, Red Fork, and Sand Springs, acres and acres of the huge white cylinders for petroleum and the white spherical tanks for natural gas remain. From the air, their circular dimensions and the equally-spaced, square bits of earth around them look like white pills set in handy travel packets. Driving by, their size is apparent as is their smell. I used to take their place in the landscape for granted, but I never liked their smell.

Yet in West Tulsa, we were proud of our city’s importance as an energy production center. It pushed us up to seventeen on the list of Cold War targets. Our eyes grew round with the thrill of facing down terror even though we knew, really, that we were safe. All we had to do, we were told, was file out of our classrooms at William Howard Taft Elementary into the single hallway, line up facing the lockers and kneel down, our heads against our knees and hands around the backs of our necks, and we would be protected from a nuclear attack.

Tulsa called itself the Oil Capital of the World, and pump jacks studded the open fields between Tulsa and Sapulpa. But although Silent Spring was published when I was five, no one in my family ever questioned the environmental connection to cancer. Not though my father’s mother died of breast cancer in her forties, Aunt Toke died of leukemia, and Dad succumbed to colon cancer at sixty-two.

Could be the Lees have the cancer gene. Speculation on Toke’s death blamed her bad burn. She’d lived in Grandad’s front bedroom for a time. He had the back one, and the story goes that one night while sweeping, her robe and nightgown caught fire from a gas heater. Grandad put out the fire by rolling her in a rug, but she never really recovered.

Most likely this is the version Jo Nell espoused. But what about her husband’s time in the oil patch, and the Sinclair Refinery located a mile from Grandad’s house?

Growing up, I saw no dichotomy between the message that Tulsa could be both the “Oil Capital of the World” and “America’s Cleanest City.” As the public service announcement on TV reminded us every night: Tulsa, America’s most beautiful city. Get to know it. Visit the Gilcrease Art Museum soon.

But after three decades of living in New York City, I’d returned with traitorous views. I was upset that fracking made Oklahoma the place in the world with the greatest number of earthquakes. I was annoyed that Oklahomans continued to elect Jim Inhofe, author of The Greatest Hoax: How the Global Warming Conspiracy Threatens Your Future, to the US Senate time after time.

Bristow’s broad, brick avenues and the buildings listed on the National Register reflected its boom years as an oil and gas town. Even after the oil played out, the town was home to refineries, pipeline facilities, and offices for petroleum-related companies.

Now, Main Street had given way to Walmart, and NAFTA had sent the Black and Decker factory to Mexico. A cousin’s husband had worked there. He said the Mexicans were so stupid they had to keep coming back to ask how things worked. But he expressed no anger toward Black and Decker, not though the woman who had inherited the car dealership in town told me the previous company rewarded workers who met or exceeded their quotas with a few hundred dollars a month. “Not much,” she said, “but it was a car payment.” Black and Decker employees couldn’t afford to buy cars. The company sent a bus to pick them up. My naiveté to imagine this eighty-five-year-old, life-long Republican in Bristow, Oklahoma would just tell me about a half-brother, who was probably half-Mexican!

Outside, the conclave of cardinals had grown to two dozen, scarlet emissaries there to give Dad’s cousin permission to tell me what happened, who the mother was, where she went, why Dad didn’t marry her. But the sliding glass doors remained closed, and the cheer-cheer-cheer went unheard. Jo Nell stood fast in her loyalty to Dad’s wish when he was alive to protect his secrets, and I presume to my mother even though Mom had what I used to call a long-hanging-down nose.

My patience worn thin, I asked her to tell me about Dad.

“Oh, your dad was ornery.” But to know how ornery I’d have to ask his high school buddies, the ones he got in trouble with.

“What do you know about Dad’s time in the Air Force?”

“I was in Germany then,” she said too quickly. “I wasn’t close to your dad.”

Only minutes earlier Jo Nell had said she arrived right around the time of her adopted daughter’s birth, which I well knew was a month after mine. If I’d felt impatience and frustration before, now I was annoyed. I called her on her blatant lie.

“You said you arrived in Germany in 1957.”

“That’s right.”

“My older brother would have been born in 1955 or 1956.”

I had documentation to prove Dad left the Air Force in 1955, and Mom had said the woman came to Tulsa to hide the pregnancy from her family and give the baby up for adoption.

Jo Nell didn’t blink. “That’s right,” she said and stuck to her lie the way wet sticks to cold even though we both knew the pale monochrome of an Oklahoma February was far from the snowy winter scene she tried to project.

Slack-jawed with disbelief, I asked for other stories. She told of a time she and Dad slid rocks down the tail fins of my grandparents’ new car. Their game left a trail of scrapes on the paint. They were four and five or five and six. My grandad only said, “You should’ve known better.”

I asked again about my Other Brother. Again she denied knowing anything, and I left Bristow feeling as though I’d just watched an episode of The Waltons, one focused on the family villains. Luther, Jim Al, and Robert Lee were bad. Jim Ross was ornery but good, and like the dew that covered their faces on summer mornings in the screened-in building, my probable brother was something we were just supposed to wipe off. “No big deal.”

Except it was a big deal. Big enough to lie about. Big enough for Dad to say a month before he died that he was grateful to Mom for never having left him, so grateful, he made sure she got the house, the commercial property, the life insurance, and a buyout of his business. He left Mom with more wealth than she’d ever had before, yet more than fifty years after she found the letters from the Mother of my Other Brother, and twenty years after his death, she’s still twisted up with anger. She threw the letters away, but as hard as she’s tried to forget, she hasn’t. And who knows what she told Jo Nell?

On the drive home, I asked about Dad’s buddies, the ones Jo Nell said he got in trouble with. But they were both dead. Then with her face to the window, Mom said she and Dad had Thanksgiving dinner with Jo Nell and her first husband in 1956. In other words, Jo Nell lied about being close to Dad around the time of my Other Brother’s birth.

“Maybe if I’d had a less sheltered upbringing, my marriage would’ve been different,” Mom added, her face still aimed at the pale February landscape.

Hard to say whether a less sheltered upbringing would have gotten her through the shock of finding letters in a dresser drawer and learning her husband’s big omission, but as I was beginning to learn, my mother often dropped breadcrumbs, a morsel here and there, pickings for the birds.