He was so tall; when I looked up at him,

in his eyes I wanted to see

the Statue of Liberty

bathed in the sunlight of his homeland.

Instead, sorrow rolled down his face,

trembling on his cheeks.

“Mỹ Lai,” he said, “I just visited Mỹ Lai.”

Then in his eyes, the photos he’d seen there

at the site of the massacre came back:

a mother clutching her son in their deaths,

bodies of barefoot women strewn across muddy paths,

naked children, cold, and silent under the feet

of American soldiers who stood and smoked.

“You weren’t involved.” I shook my head. “It was the war.”

Yet he trembled. It had taken him forty-two years to come back;

each of his days filled with nightmare

and the fear that some Vietnamese

would run him down with knives on the street.

I wanted to say something else, but words didn’t come,

so I pulled him into the stream of life

rushing around us: women balancing baskets of bursting flowers

on their slender shoulders, men cycling autumn away on their cyclos,

girls giggling their way to school, their áo dài dresses

fluttering like wings of white doves.

“This was a war zone when I left,”

he muttered as we passed

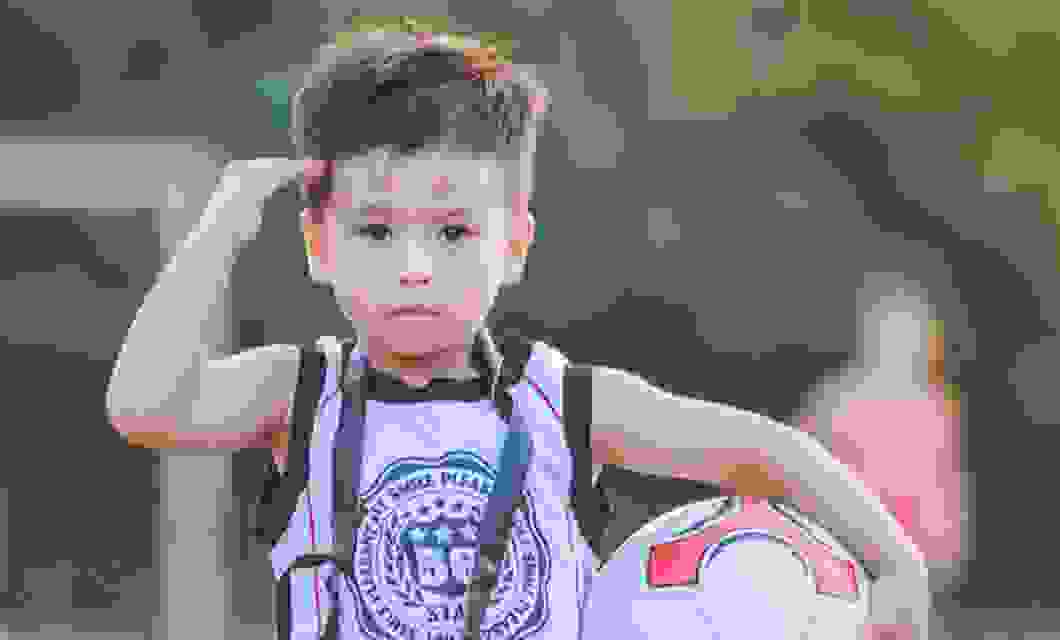

a group of boys who stood in a circle,

kicking a feathered ball to each other,

their laughter spiraling upward.

He jumped back as the feathered ball flew towards us.

“Kick it, Uncle, kick it,” the boys called out to him in Vietnamese,

their arms stretching, pleading.

For a moment, he stood as if fear

had frozen inside of him.

The feathered ball dipped, spinning fast for the ground.

Suddenly his foot reached forward;

the ball was lifted

above sunlight.