Chapter One of an "in process" memoir

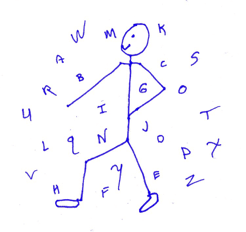

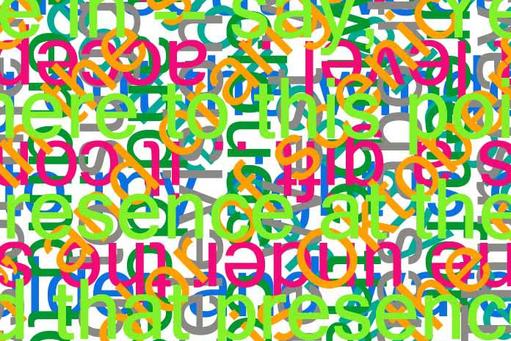

I can’t read more than two pages without a break. Yet, the form of word has always held my attention. My earliest memory of reading is seeing nothing but letters. I walked through a city of capital Bs and stepped over lower case gs watching Ss swirl overhead and js chase the quirky qs. I held an open book on my lap and fell into the dance of letters on the page. Letters that moved when touched by adjacent characters—tall and small, 30-point and 12, Times New Roman and Arial.

Dancing with letters was the good about reading. The bad stood as Miss Jones, my second grade teacher. She was as crabby as she was beautiful—tall and slender with short, perky hair the color of a black crayon. I sensed she didn’t like me or any of the children in her class. To my eyes, she saw me as BAD. After reading Fun With Dick and Jane (oh, how I loved Dick and Jane) she insisted, “Letters stick together to form words, Lissa.” Oh, my gosh, she knew my letters played on the page! She knew I was not good.

I sensed deep down that there was a blockage of some kind between my brain and words printed on the page. I remember the personal disappointment that I couldn’t get it—reading wasn’t coming along for me as it was for my classmates. I can touch the edge of that sadness and remember the ache as I sat with it not knowing what else to do.

Tenderly, I remember the Yellow Bird reading group. In a dream, I see us sitting on a low riser—the first row of audience participation reserved for “special readers.” I watch the parade of the alphabet’s 26 letters march by as they change into limitless combinations displayed within pigments of color.

You know those plastic magnetic letters that children play with on refrigerator doors? Letters felt like that to me—like I could stick them on my forehead and move them into various spaces of play right there above my eyes. They were pieces of energy, each one a bit different from the next. Letters were objects of endless possibility.

I suppose creative vision arises in as many ways as people differ and that each one of us is born with challenges and gifts. Like slow-rising dough, the gift within dyslexia waited patiently for me to discover more to a grouping of letters than the inharmonious sounding-out of words.

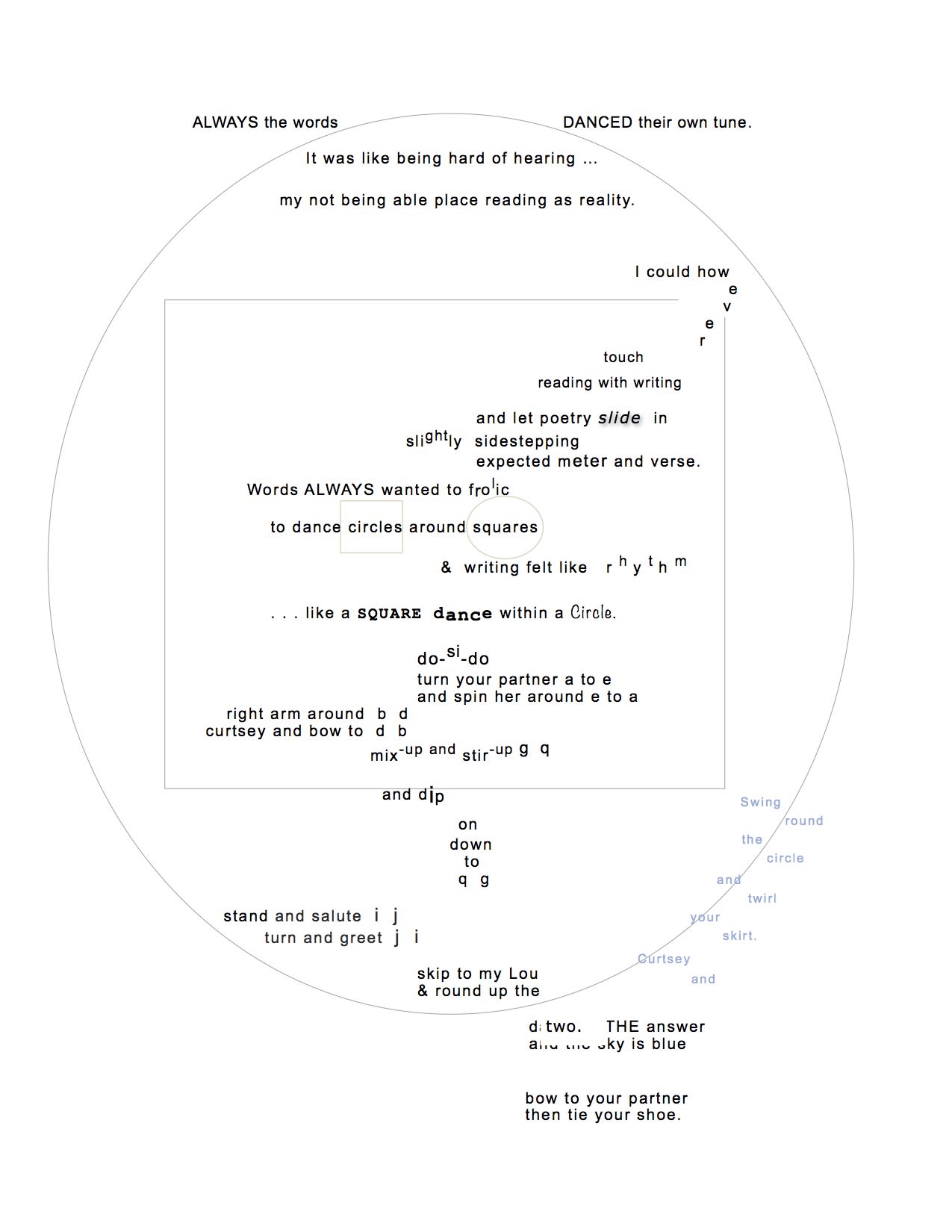

Square Dance of the Yellow Birds

I was assigned to the Yellow Bird reading group—not the Red Bird or the rather brusque Blue Jay group where smart kids sat moving their lips as they read out loud. I’d watch the “page turners” from my desk of boredom as their pages turned at the same time!

My Yellow Bird associates were boys who squirmed and wiggled and were told to “sit still” every three minutes. I, the Yellow Bird in a skirt my mother had pressed before school, sat oh so still and sometimes yearned to be just Red—not wanting to push my luck to Blue. With legs folded underneath, I sat in a circle with the boys on the cold brown linoleum floor in room 2-A. I sat there thinking about those interesting shapes upon the page—those letters within the words.

Dyslexia has always been the edge of my life—it bounds everything else. Learning to read felt much like being on roller skates in a rink of fast moving others, while a slow moving me struggled just to keep legs and wits together. If words offered nothing more than the struggle to read, my world would be gray. Introduction to reading was an exhausting battle in which winning came hard. Conversely, inside each troubling word, creativity winked. On top of the struggle was dance. Art was waiting for me because fearful Friday spelling bees and flash card contests did not inspire. The chaotic and confused years of having a brain that refused to be driven to the expected, drove me to the surprise of creative awakening and delight in self.

Reading was not my reality—the real was a poetic listening to text within artistic vision. I didn’t know to call it poetry when text sounded lyrical and had the look of my mother’s sheet music lying on the piano. Poetry is not straightforward. The schoolgirl me and the adult me meet in a reflection of personal experience with word. Then, as now, I select and write words that fit my voice. Poetry slides in while sidestepping expected style and verse.

Survival skills

Standardized tests were my nemesis. I never did well filling in tiny ovals with the worn lead of a No.2 pencil. I’m remembering how I slipped out of taking the ACT for college admission.

During both my junior and senior years of high school, I registered to take the ACT, a college requirement. I worried my way past the test dates (and the make-up test dates) for both years. As painful as the avoidance was, it was preferable to taking the exam. I dreaded the math word problems and having to read and re-read the confusing situational conundrums. The reading comprehension segment might as well have been written in Swahili. How could I answer such detailed questions about “the above paragraph” without re-reading sentence by sentence to find the answer to match the question?

On June 8, 1966, the horrific Topeka Tornado came roaring through the city, cutting a swath from southwest to northeast. The midpoint of destruction was Washburn University, the last municipal university in the United States and the school from which I received admission—contingent upon receipt of my ACT scores.

The fall semester at Washburn was tenaciously on schedule with most offices and classrooms located in double-wide trailers. These square metal trailers were painted white, placed along university sidewalks and became our temporary campus.

What did I do about my missing ACT test results? I spoke with my academic advisor and suggested that it was possible, wasn’t it, that my test scores had become part of the rubble where classroom and office buildings once stood? It was possible that my scores had been in the now obliterated file cabinets shredded amongst tree limbs and broken glass or, could my scores have traveled downtown on the wind to become enmeshed in the soggy mess of Kansas Avenue?

Either my feeble excuses for having no test results were so lame that he felt sorry for me or he considered the possibility of my test scores getting caught within the tornadic funnel or whatever, he signed my schedule which allowed me to attend classes.

More than dishonesty, this ACT caper has to do with adaptation — firsthand experience of what happens when a student is forever hammered for not being “average.” I still believe that the probability of someone like me getting into college in 1966 was close to zero. I slipped through the door simply because electronic records were not accessible at that time.

Miracles are the rule, not the exception

As an adult, I loved libraries but for the non-fiction section in the Ann Arbor Public Library. It was frightful. Seriously, I avoided going to this second floor collection because I considered myself too dumb to deal with the sophisticated arrangement of books on the shelves and I didn’t know how put a question to the librarians. They were busy researching solid questions from well-educated folk who felt at home sitting at the oak tables surrounded by volumes marked with Dewey's decimals.

I applied for and got a new job at the neighborhood branch library where I shelved books hoping to learn exactly how the nonfiction books were arranged thus dispelling the anxiety about my ability to navigate through isles of thought provoking books. Two years later, my love for all things word joined with the experience of working in a library and pointed me in the direction of librarianship. I applied for the Library Science program at the University of Michigan. After a six week wait during which I came to firmly believe that miracles did not happen to people like me, there was a letter in the mail from the University. Rather than wait until I was sitting down, I tore into the envelop and . . . I was accepted into library school!

In graduate school I experienced a transformative process in reading and writing through the keyboard and monitor—computers were just beginning to enter classrooms around the country. The computer offered me a way out of the dyslexic world of slow-moving thought. Reading on the computer energized me. The letters stood out and the words were readable—my eyes remained alert rather than drifting into dopiness. I had found “my tool” and a connection to the reading world. A miracle.

The Varieties of Reading Experience

The beginning is word. Within my worldview, this truth is rather odd unless word means more than text. Formulas and symbols that represent words and concepts were deeply satisfying to me. The large periodic table that hung on the front wall in the high school chemistry lab also hangs somewhere in my head. Chemistry, logic and statistics made sense to me.

I exist within a phrase of literacy that is about fitting the pieces of reading and writing into a scheme that makes sense to me. Somewhat like online magnetic poetry where words are moved around the screen to make poems. One day the words came together: I Write Art.

Dyslexia and the experience of creativity

I was taught to read one word after another in a linear style. Dyslexia hampers reading speed and comprehension because once the wandering mind arrives at the end of a sentence, the starting point has been forgotten.

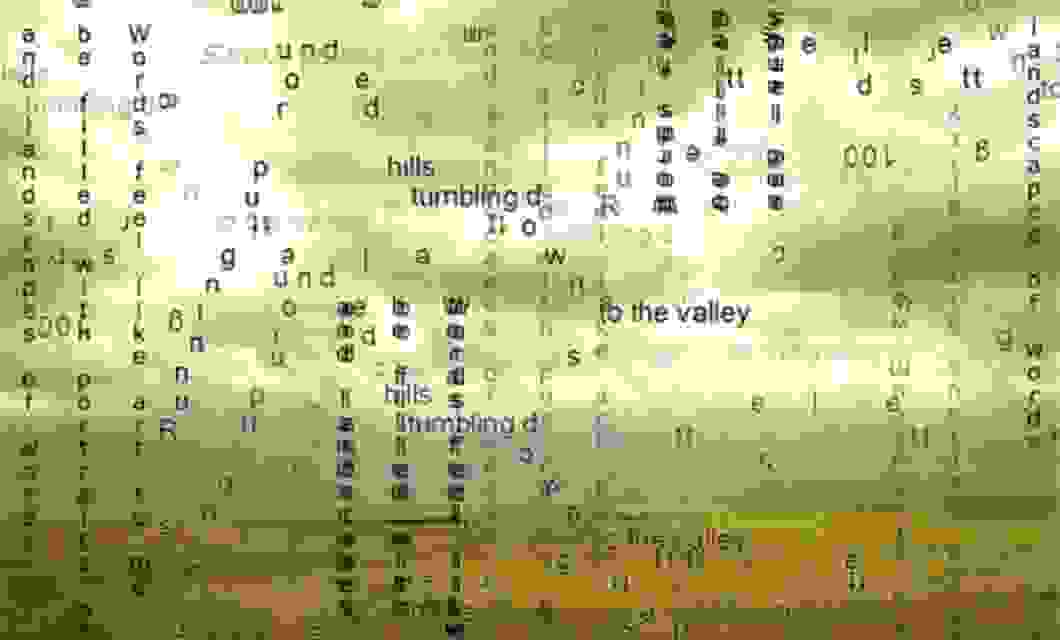

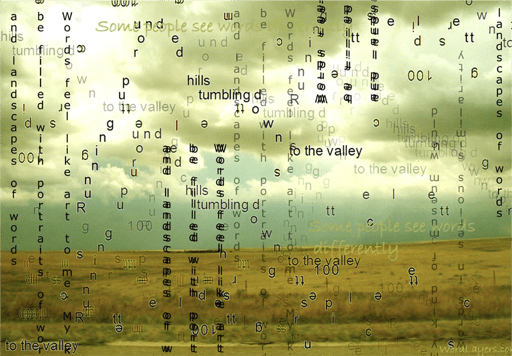

Artistically, I tried writing in layers as a form of writing with visual depth. WordLayers is a mode of expression as linear lines of text are written over previously written lines of text. The eye travels vertically and reading becomes sensation rather than literate. Vertical text places attention on the freedom of creative word. The emphasis moves to depth and writing becomes private. This method frees the mind and thought becomes loose and boundaries defining what should and should not be said begin to dissolve.

The image above consists of seven days of writing one topic per day. Each day’s entry is written on top of the day before. Writing becomes personal and private and reading turns toward what you want it to be. Word can become art with no explanation.

I discovered that this form of self communication worked nicely when writing down decisions or problems. Word over word and line over line not only makes for an artful work but also is healing and fulfilling at the same time. Color adds spice and dance to the whole and fits within the mood of the written thoughts.

HTML and WordLayers

I remember the boss who presented me with a new language. “Here is the latest download on HTML to get you started.” With this no turning-back push, he led a small army of library workers into the brave new world of the Internet. The process of integrating computer code with existing textual language took days of staring into the monitor way past HTML for Dummies. After three days, I took my first conscious breath. “Be with it, you don’t have to understand why it works, just know that. . .it works.” I relaxed into the task and built a reference database suitable for graphical browsing. Below is a sample of HTML code from the original WordLayers.com.

<table border="0" width="579" > <bgcolor=”#FFFFFF”> <tbody> <tr> <td> <p> <align="center"> <font size="7" face="Lucida Calligraphy"><b>

<a href="thumbnails.htm"> WordLayers</a></b> </font> </td> </tr> <center> <tr> <td> <align=”center”> <a href="thumbnails.htm"> <img border="0" src="Images/cats-eye-sm5.jpg"></a></td> </tr> <td width="284""> <font size="5" face="Lucida handwriting"> Journaling<br> Words into<br> Art</font></td></tr></center></table>

Look familiar? Inside my head, yes. It is writing that must be read in gulps. To my eyes, HTML is WordLayers. Reading is the process of understanding the code of inside out.

WordLayers is a reflection of the way I learned to read on the computer: vertically and into the whole of text. Reading from a computer monitor is like swallowing words by the screen-full.

Words feel like art to me

A couple of summers ago, my husband and I were returning to Kansas City from Estes Park, Colorado. Most of the drive home was spent in and out of thunderstorms between which we were privy to prairie colors under wet sun. I took several photos and captured a scene that looks almost as good as it felt on that late August afternoon just outside Colby, Kansas. I had written a bit in my journal—something about words raining down onto golden fields of cut wheat. Days later, I wrote on top of the printed landscape "some people see words differently" and on top of this, words from a poem rained down on the image which, eventually, became the art print that now hangs on our living room wall. Certainly, dyslexia appears as disorder to discerning outside eyes. However, many artists see this different-ness as creativity from the inside out.

In Conclusion

Dyslexia makes life difficult. It affects the ability to read and to hear spoken word properly. It hampers communication within yourself and with other individuals. WordLayers developed within me several years ago when I began to make art with words. Writing word on word is a vertical dive into the artistic interpretation of word itself. At times the entire scope of word disappears and the reading of art remains.