“Swearing is lip filth”

Said the sign above the doorway of the YMCA. We all were guilty of cussing, but we did not swear. At least I didn’t, I swear.

Across the street from the Y sat the silent, lonely, red-brick building with granite columns.

It was an oasis, nothing less: The Paul Laurence Dunbar Branch Library. Hemingway’s clean well-lighted place in a large, red-brick WPA-era building set on the high side of a segregated ghetto valley colloquially known as the whores’ stroll. A mysterious kind of pause amid all the other commercial and deserted buildings.

I discovered it at twilight one fall evening, running for my life from some teenaged predators bent on taking whatever money I might possess. I took a sharp turn and crossed the street from the Kappa Lounge, then raced up the stairs of the library and hid behind one of its great columns.

They were in the WPA-Greek tradition and framed the huge wooden door that opened onto the library’s vestibule. The thugs stopped in dead out on the sidewalk, and would not take another step in the direction of the building.

The Dunbar was a mystery to most all of us in the neighborhood, but I was stunned by the effect on the assholes chasing me.

I was so fascinated, I stepped out from behind the column and took another look at the library’s limestone engraved named on the lentil over the door, wondering what the heck. The bullies raced away, on down the hill. I backed into the library door, turned, and opened it.

What I beheld became my personal safe harbor for the next several years. A hallowed place of quiet peace, set in the warm rich glow of polished hardwood and golden lamplight, amidst the noise and constant turmoil of my childhood world. Early on, I decided that since I was pretty much stuck at the Dunbar library, I might as well read some of the books. I got started traveling the world via National Geographic.

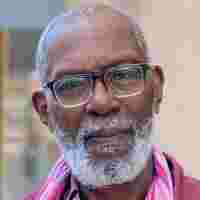

A few months later, my best friend and I were about to leave Dunbar elementary school for summer vacation. We decided to say a last goodbye to our teacher and went up to her classroom. She was there, boxing up books and other learning materials. A tall, erect, handsome woman with silver streaked hair and a voice worthy of Broadway. Miss Townsend. She wished us well, then paused and fished into one of her boxes.

“Here, Vernon,” she said to my friend, handing him a book. “Uncle Funny Bunny,” the title read.

“If you’ll complete this workbook over the summer, you’ll be well prepared for next school year.”

“Thank you, Miss Townsend,” Vernon said, nervously aware of my invisibility. Miss Townsend was a severe woman, capable of violent anger. I stood there waiting for my ”Uncle Funny Bunny” book. But, the old spinster turned away, and resumed boxing up books.

“Have a safe summer, boys,” she said dismissively.

“Yes, m’am,” Vernon said as we walked away.

I did okay until we got out of the building, whereupon I started to cry quietly.

“Hey man, you can have this old book,” Vernon offered. “I can get one from my Momma.”

His mother was a teacher at another school.

But, I declined.

“No, I know a lady who’ll loan me all the books I need,” I said.

“And I’m gonna read ‘em all."

Except for the Y, there was no place as safe out of school as the Dunbar Branch Library. Named after the venerable lyric poet from Ohio. And once I discovered I could escape the routine violence and vice of my immediate environment, I spent nearly every weekday evening—and many a summer afternoon—there in the quiet company of the librarian and a few elders.

In March, just after the first wave of Beatlemania, the sun had just begun to return.

Walking home from the library, passing the corner on which King Kelly held court.

I found myself summoned by the shoeshine king.

Hey youngblood, he called out.

Come here and let me holla atcha for a few.

I sidled over cautiously. He was a friend of Daddy’s, so I dared not disrespect him, even though Everyone said he was crazy. After all, he called himself the shoeshine king.

I noticed you been patronizin’ the old Dunbar library quite a bit, he said or asked.

Well, I go there a lot, I answered carefully.

I helped build that sucker after the war, he said.

I cooked for Ike, all over Europe, y’know.

Went all over the world with him.

You Mack’s boy, aintcha?

Yessir, nodding.

Well, you give my regards to your mama and daddy.

And watch what you read up yonder. That shit can give a brother notions.

Know what I mean?

Yessir, no idea what he was babbling ‘bout.

But it sounded like notions were to be avoided at all costs.

I proceeded mindfully, keeping a close eye out for any notions that might beset me.

Her name was Gertrude Richards, the Dunbar Branch Librarian. I’ll never forget our time together in that venerable sanctuary. Cool quiet summer afternoons, long autumn evenings, frosty winter twilights when snow hung in the library’s sentinel evergreens as if in a postcard scene offset by the dark brick building. Peaceful hours when it seemed there was no one else in the world but Miss Richards and me. When the library closed each night, I’d race home through the darkness, armed with words, words, words; and increasingly, ‘notions.’

They kinda eased their way into me.

One autumn evening, I picked up an anthology of long-dead white cats and let it fall open, to lead me to an unknown poem. It lead to “Song” by old John Donne. As I began to read “Song,” my eyes fell on a slender volume named “A Coney Island of the Mind,” which I snatched off the shelf eagerly because of its title. It fell open to a poem with a number as its title: #23.

The adult section.

The Adult Section had been an ongoing reading chess match between Miss Richards since I received my library card. Every time I made a move in the direction of that section, Miss Richards headed me off, usually with a suggestion like “Treasure Island,” “Robin Hood,” or something. I always accepted her suggestions, but never ceased my quest for the Adult section.

The autumn evening I discovered those two vastly different poems was the first time I succeeded in catching her distracted by her own reading to sneak into it.

Suffice it to say, it was not what I’d been imagining for years.

But my immediate understanding of the two poems, separated by more than 300 years, made it clear why Miss Richards had both protected me from and prepared me for the Adult section. My immediate and innate understanding of both poems and their poets opened a doorway inside me: A doorway for which I’d never find an exit.

I remember thinking, “Wow! This shit is important.” It did not feel like a wise career pursuit; but it sure felt as if someone had to do it. It was the ‘60s. America had already convinced me that as its designated “nigger” I had nothing to lose. So I picked up the gauntlet.

As years passed, I discovered the football field, pool hall, and other spaces into which I wedged myself, but my natural connection to the library held firm. Over the decades that followed, wherever I lived long enough to pay utilities I acquired a library card. Got myself a veritable trove of ‘em. From Wichita to points east and west. I armored myself with all I learned in every library I could find everywhere I lived.

When I graduated from high school, I visited Miss Richards, to tell her I was off to college. She wept.

Months later, riding out of the City on the old Santa Fe train, I vivdly recall excitedly thinking, “I’m off to college! Man, I ain’t never eatin’ beans or listening to the Blues again.” Little did I know, y’know. The Blues are one thing, but sadness is another thing entirely. I was on my way to learning the difference.

And when I did, I raced back into the Blues’ embrace with a full heart.

(for the pool players)

I play it cool, and dig all jive.

That’s the reason I stay alive.

My motto as I live and learn is dig

And be dug in return.

Coming into our own midway thru high school. Old enough and respectful enough to be allowed to shoot pool at Brown’s after school, when we shoulda been doing homework. Studying the angles of street geometry, you might say. Not hanging out at the Library as much. But being sent back to it more and more, as I grew, and was made more aware of my world.

Hey!

Youngblood. What they teachin’ y’all over there at Carter G. Woodson school?

Called out one of the poolhall’s regular hustlers.

History, one of us responded.

O yeah? What kinda History? History or his story?

You know Carter G. Woodson was a historian, right?

I cleared my throat and said Lewis and Clark right now. I was actually enjoying the subject.

Well, then you must already be hip to York, right?

Who? we all asked. Me, Doc, and Heywood, playing for quarters.

Who!? Who? You sound like a bunch of hoot-owls.

Who the hell is y’all’s history teacher?

Mr. Clark we answered.

Mr. Clark? James Clark, Deacon over at Calvary?

He seemed outraged. Yessir, I managed.

Well, ain’t that a bitch? I played football with that nigger. You tell Mr. Clark that Blue Hill said the next time you fellas are asked about York, Hannibal, or the Buffalo Soldiers, y’all better have a cogent comprehensive answer.

Got me? Co-gent and com-pre-hensive!

Yessir.

Give your old man my regards.

Your Mama too.

Yessir.

I was soon back in the library. But York wasn’t there.

Editor's Note: We publish this work as a tribute to Morris, who passed away in September 2024 … our words live on even after we make the final transition.