or What Happened at the Wedding

The man had belly pains. He told his daughter and she took him to the Emergency Room. The doc told them to go back to the party.

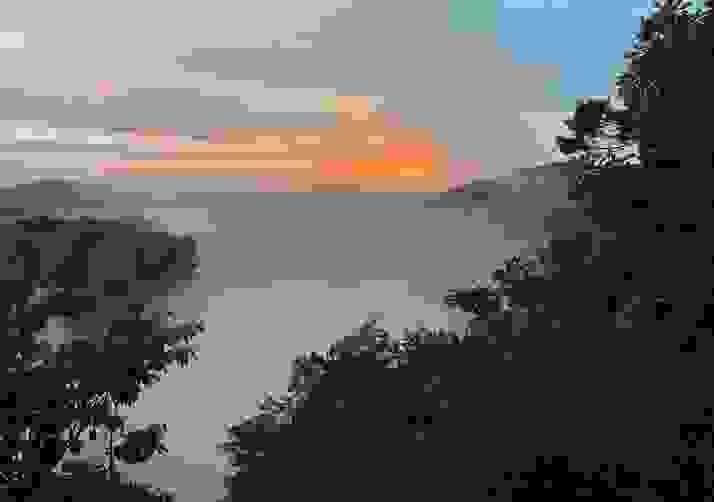

They’d been at a wedding at a castle in Indiana. The proprietor had built the castle from river rocks and cement bricks molded in half-gallon milk cartons. When the cement had set, the clever man had peeled away the cardboard, leaving him with more materials for his dream. He’d always wanted to build a castle, and now it was done. Inside, the dust lay in thick layers. Brides and grooms came anyway—the dirt added to the realism of the faux-medieval setting. They should have strewn rushes and rosemary too. I forget the owner/builder/dreamer’s name. You see, this happened some very long time ago.

The pains came at each meal. The father told the daughter his chest had turned purple, but the girl could see no color. She wondered if the pains were guilt—her guilt—for not having called often enough. She lived in Oklahoma; her father lived in Ohio. They’d met up in Indiana, to see a granddaughter married. Well, his granddaughter, her niece. Her sister’s only living child.

I suppose you want the father to have a name, but he’s just like any doting, aging man. The daughter you may call Mississippi, or Missy for short, because her mother’d had a humor. The mother, who was unlike any mother in the world, did not know when to quit and thus died. She died and the father bought more chickens, planted the garden, started dating on the internet. Missy missed the dating boat altogether, online or otherwise. I’d like to say she had a cat or two, but she didn’t. She didn’t even have a fish, because after all that healthy farmwork as a daughter, she didn’t care for animals in the house. They stank, and peed and pooped in places that made the house stink.

You want me to tell you that Missy was absent but dutiful, that she cared for her family, though her work required her to live elsewhere. She was moving to California soon, to write; the trip between the Midwest and the West Coast would be even more difficult for everyone. The cost, astronomical. But her father would save up and visit for better weather, she guessed. He’d take her to the parks where he’d played in amateur tennis tournaments as a young man. He’d lived there many years ago, also as a writer of sorts. Of code, in fact, but now fully retired. He puttered now. He retiled bathrooms, lent the tractor to the neighbor who still cut his own hay. But hay is boring, and so is Indiana. Even a handmade castle erected on the flat plains of Indiana is boring, if nothing ever happens there except weddings. What a wedding, though! The wedding of a lifetime, I’d say. Yeah, I’d say it still.

You sure act like you want to know these people, but I barely knew them myself. I don’t know what else to tell you other than what I was told and then, what happened at the wedding.

I’d gone with my spouse, who was of distant relation to the groom. You may read all about this in some fat novel one day soon, but for right now, let’s call the groom Thorn and the bride Rose. Thorn didn’t recognize my wife, so long as it had been since they’d seen each other. This time, my wife exclaimed something like “Those cute little green dungarees!” and the groom blushed. The groom’s parents had passed on too, old hippies to the end, buried under the same tree in the bleak, frozen woods. I forget how my wife knew the groom’s family, but that’s also very boring.

The groom wore a wool kilt, because that’s what all the handsome hipsters did back then, and the bride’s grandfather wheezed on some bagpipes. I didn’t know about his purple chest yet, but my lord, if you’d heard him, you’d have believed him, unlike Missy. Missy had care of him, so that her sister and her sister’s daughter—the bride, of course—could get on with the nuptials. Next to Thorn, Rose seemed a stick-in-the-mud with her no-frills white gown and blue garter. A traditionalist, to be sure, from farmer’s stock. Never mind the two toddlers as flower girls. No one minded bastards anymore. My wife told me not to use that word with exact reference. I told her to refill my flask while we waited interminably in what was meant to be the grand hall. Let me tell you, a homemade dreamed-up castle can barely support a hall, much less a grand one. No room for chairs, we all stood, shifting foot to foot on the river stone, rounding our flat arches to fit the cold, uneven floor. I can still hear our soles cracking, we stood there so fucking long.

This story makes me sound old, and crotchety, so far, but what I’m about to tell you will change your mind, will put a little peck in your pecker, if you know what I mean. I didn’t catch the garter, but I caught something else. I caught the bride’s eye as she descended the stone stairs like a church aisle. Leisurely, but sliding each foot so it caught each step, looking straight at me. I smiled and something in her face lit like fireworks. Maybe I reminded her of her grandfather, who by now stood clutching his deflated pipes to his purple torso. She smiled and something crackled in me too, but it didn’t feel fatherly, or even avuncular. My wife saw and pinched me, hard, on the behind. I sniggered aloud and she pinched me again on the back of the biceps, in that vulnerable spot where the skin had started to sag as my man-muscles wasted away. I thought of Rose then as a thrill-seeking, night-blooming flower—a stolen, broken-into blossom. She glowed muzzy white in the hall’s dimness, just like the way the moon might favor a field laid fallow.

Ah, you younger than me begrudge me my poetry, but I tell you, she was a poet’s hart. No, not the organ, but the animal. The deer that haunts the wilderness, fleeing from danger, returning to mate from nature, from necessity. No, I’m not mixing my metaphors—Rose had all the virility in this instance. Mine was residual, an echo, lost somewhere between my wife’s legs.

I watched Rose all though the ceremony, my wife sighing at my side. She huffed at me, but she sighed for the bride. She remembered her own posy of daisies, her own bridal glory. I remembered too—I still loved her witty blitheness, her plush curves. But this bride, this Rose, had wrestled my soul into a contortion, if only for one night. I watched her kiss Thorn, burning.

We ate free-range fried chicken legs on picnic tables outside on the damp castle grounds. They’d lugged in gas heaters, and with light jackets, we felt cozy, warmer outside than inside the castle’s milk-carton walls. The mother of the bride—Missy’s sister, you may recall—filled flutes to the brim, spilling prosecco down our wrists and laughing as we licked. I chased my chicken with their bubbly wine and then my own whiskey. We all got drunk, Rose and Thorn dancing with each other and with Rose’s grandfather and Rose’s mother and eventually Rose’s sister. The bride and groom never stopped dancing, forcing new partners into lumbering threesomes. To their joint marital bosom, they clutched grade-school cronies, long-lost college roommates, obscure relatives. The spawn of Rose and Thorn danced too, tripping up their parents’ partners. I asked my wife if I should be so bold as to expect a turn in the lovely couple’s sweaty embrace. She said she had a carbonation headache and bounced off to bed in our borrowed pop-up camper. I knew our friends back home, the lenders, both smoked and had dogs. I was in no hurry to retire.

Pretending to blearily check the time on my watch, I watched Rose and Thorn sneak away from the party. They melted and merged into the castle, dark shadows against gray stones, even in their bright garb and giddiness. Rose felt like a specter to me then—a futile presence. Others faded away when a car pulled up into the gravel lot. I’d not noticed the car leave earlier, but now it was back, nevertheless. Missy emerged to lead her father to the castle, then returned to plop down beside me; she saw my sad, floppy jowls and lifted a hand to my cheek. She scratched at my wiry beard. She was stone sober, and not entirely unbrave. Missy, she said. I know, I said.

She eyed me like a dog waiting for scraps. John, I wanted to tell her, but I figured names were just names, by then. No meaning, no stronghold. Not even in the middle of the middle—the middle of the state, the middle of the country. Where were we, anyhow? How’d I get there?

Instead, I handed her my flask. She sipped, opened her mouth as if to emit dragon fire. A polite burp rolled out instead. I patted her knee when she cupped the metal, warm in her hands. She told me everything I told you earlier—her father’s purple pain, her filial guilt, her writing, her lonely. I didn’t want to come to this wedding, she said. But I’m glad you did, I said. Then we walked together, into the woods, and I held her snug against a tree when the heat left our bodies.